297- La Cucaracha, a house on wheels | OVERLAND JOURNAL

Published first at Overland Journal, Fall Issue 2015. Written by Chris Collard. Photography by Pablo Rey and Chris Collard.

•••••

LA CUCARACHA: 15 YEARS, 50 COUNTRIES, 330,000 KILOMETERS, AND A DRIVE-THRU WEDDING.

Why We Love la Cucaracha (©PabloRey)

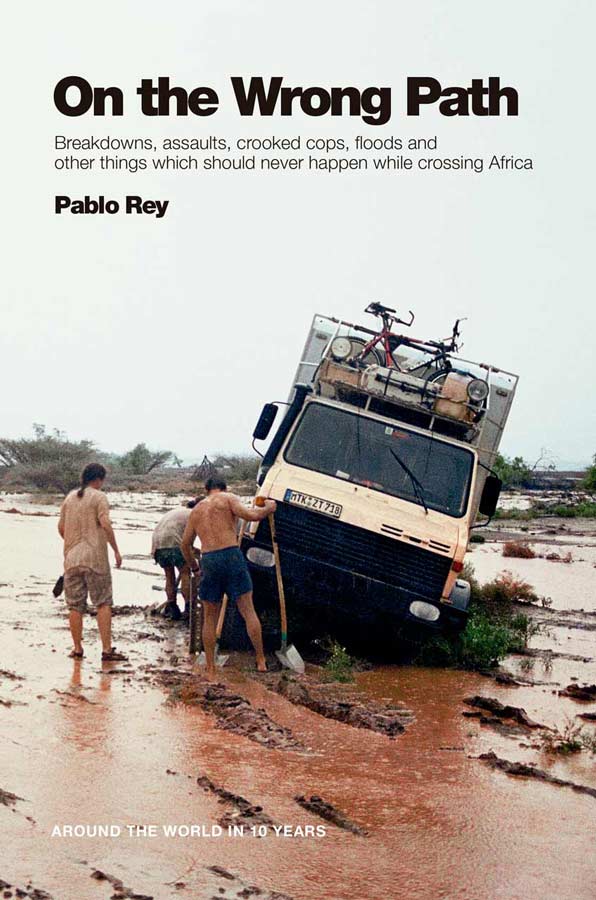

La Cucaracha has its own personality and idiosyncrasies. We have loved and hated it, often in the same day. There was a time when we wanted to throw it off a cliff and cash in on an imaginary insurance claim. We’ve had a few major breakdowns: in the Sudanese Sahara, Kenya’s Sibiloi National Park, on the Bolivian Altiplano, and again in the Chilean Andes. When the springs broke in Mozambique, we travelled almost 1000 kilometers with them attached with wire until we found a used replacement set as a permanent repair. After the motor died in Iquique, Chile, we installed a second-hand motor – a great junkyard find. That was nine years and 200,000 kilometers ago. Once we learned how to drive and care for it, la Cucaracha became a third member of the family and problems stopped.

It had previously been known as the Cow (it is very heavy), the Dragon (it smokes a lot), and the Mitsushiti (it broke down a lot). We found the perfect name, la Cucaracha (the cockroach), while travelling in Colombia. Like a cockroach, it is small, can stealthily sneak into any space, and survives anything – even us.

We appreciate that it has a short wheelbase, fits perfectly in a shipping container, the bed is always made, and we can watch the moon through the sunroof at night. We have slept in la Cucaracha for more nights than in any of the conventional brick houses we have lived in. We have shipped it twice: the first was from Cape Town to Buenos Aires (for a reduced price), and again from the Guajira Peninsula, Colombia, to Colón, Panama (for free), where it was tied to the deck of an empty Bolivian cargo ship named Intrepide. It has been our only four-wheel drive, and has taken us to the ends of the world.

LA CUCARACHA ©ChrisCollard

Though many of us dream about building the perfect rig for that “big trip” around the world, few actually act upon that dream and see it to fruition. This was not the case for Pablo Rey, a creative advertising consultant who was suffering from an acute case of career burnout. In 1999, during an off-the-cuff trip to Southern Africa, he had an epiphany: to see the African continent in greater detail and never to buy a return ticket again. Though he did find himself back home in Barcelona, Spain, it didn’t take him long to quit his job, buy a vehicle, and talk his sweetheart Anna into trading professional life for that of a vagabond. The latter was a bit of a challenge. Pablo recalled, “I remember the look on Anna’s face like she was in front of me today. It said, ‘Drive around the world! How? With what money? Toward where? What did you hit your head against?’ He reasoned with her, “Almost every country in the world is connected to another by a road, thus nearly every road in the world starts at the door of your house.”

Their original 1-year plan to experience Africa on an intimate level while taking as many turns as possible morphed into two and a half years, and then expanded to include South America. Two more years passed, then another three, and they were still embracing their nomadic existence. They eventually realized that life on the road wasn’t simply an extended vacation or escape from reality – it was reality.

La Cucaracha, a 1991 Mitsubishi L300 Delica four-wheel drive van, wasn’t gleaming gem when Pablo plunked down $10,000 and the wayward duo drove it into the new millennium. The soon-to-be world-travelling insect was second-hand, bone stock, and lacked nearly all of the items many of us deem as necessities. Rather than spending months prepping the vehicle, they decided to keep up with the speed of life, get on the road, and make modifications as the trip progressed and needs arose. The bull bar was fabricated in Chile ($100), the fancy snorkel was crafted from 3-inch steel pipe in a shop in Bulawayo, Zimbabwe ($40), and an aluminum storage box was added in Buenos Aires, Argentina (free). The yellow tow bar (which after nine years has only recently put to use), was received as a gift from a friend in the Atacama Desert.

¶

They eventually realized that life on the road wasn’t simply an extended vacation or escape from reality – it was reality.

¶

La Cucaracha’s drivetrain remains in factory form; a good thing since Pablo readily admits that he is not a mechanic. In contrast to the normal male/female roles, Anna, who completed a course on automotive maintenance, manages most of the mechanical issues. Pablo, the creative one, focuses his energy on photographing the journey and penning books on their adventures.

A peek inside reveals the epitome of function and efficiency. If you think about it, travelling year-in and year-out requires one to carry clothing and equipment for all seasons. Every item has a specific space and there is a place for every item. They don’t travel with an ice chest or electric fridge/freezer, as this would occupy too much real estate. As a result they eat a lot of fresh food. The galley consists of a homemade single-burner stove, 6-liter propane bottle, and a small plastic storage bin for pots and pans. Sundries and clothing are stored under the foot of the bed in used aluminum boxes from Panama Jack. Moving rearward there is a home-fabricated wood storage compartment that contains everything from shoes and spare parts, to tools and bundles of books. Out back are two slide-in plastic crates with maps, more tools, and automotive fluids. Throw a 3-inch foam pad on top and you have a bed for two. The shovel, camp chairs, sunshade, window cleaner, and a host of other knickknacks reside in a cubby. On the starboard side is a hands-in (opposed to walk-in) closet stuffed with bins, bags, toilet tissue and blankets. To port is a world map with a thin spaghetti-line representing the trio’s 15 years of wandering the globe.

More conventional upgrades include General Grabber AT2 all-terrain tires and Baja Design LED lights. After meeting Sergio Murillo, owner of BajaRack, at Overland Expo, la Cucaracha found its way to Ensenada, Mexico, where Sergio and his team fitted it with a custom roof rack designed to provide a full view of the heavens through the sunroof. Peeling away the canvas tarp (a used roof top tent cover) reveals fold-up bicycles, backpacks, sleeping pads and bags, and emergency fuel.

Due to sticky hands in many parts of the world, five of the vehicle’s windows are plated with aluminum, and basic latches and padlocks secure the doors. None are elegant, but all fulfill the requirement. Because it is illegal to possess a firearm in many countries, added security is in the form of Pablo’s favorite ninja golf club and Anna’s “quick draw” bear-grade pepper spray – both of which have been utilized with full effect.

¶

Pablo and Anna maintain that you will only regret the things you didn’t do – never the things you tried and failed to do.

¶

One might wonder how la Cucaracha finances its travels – a good question for those who possess “the dream.” The first rule of engagement is to align oneself with humans that don’t require filet mignon every night. The second is to influence them to work. Though most of the couple’s time is spent moving slowly while taking as many turns as possible, Pablo has written several books and is a regular contributor to publications around the world. Anna picks up contract work with a concert promoter in Spain, and weaves colorful bracelets and necklaces. If you run into them on the road, they may be sitting on a street corner in front of la Cucaracha peddling their wares.

This June marked their 15th year on the road, living together at arm’s length in a 5-square meter van. They are true nomads, and recently confirmed their love for the road (and each other) by taking a right turn into a drive-through chapel in Las Vegas and tying the knot. La Cucaracha (who performed the duties of best man, father of the groom, bridesmaid, witness, and only guest) has carried the pair 330,000 kilometers through more than 50 countries. Its body carries battle scars from flying stones in Kenya and Ethiopia (unfriendly locals), rogue tree trunks in South America, and boulders in Canyonlands National Park, Utah. Disguising these blemishes are tattoos of cave paintings in Zimbabwe, Moche snakes of Peru, sleeping banditos, and cactus from Mexico. Though life on the road – in close proximity to your two best (and worst) friends – may not always be a bowl of cherries, Pablo and Anna maintain that you will only regret the things you didn’t do – never the things you tried and failed to do. Good words to live by.

Specifications

- 1991 Mitsubishi L300 Delica GLX 4WD

- Engine: D4D56 2.5-liter 4-cylinder diesel

- Transmission: 5-speed manual

- Fuel cell/range: 130-liter/1,100 km

- Roof storage: Baja Rack custom

- Suspension: front torsion bars, rear leafs

- Bumpers: Chilean homemade

- Tires/wheels: General Grabber AT2, OE

- Batteries: Optima Yellow Top (2), Red Top (1), manual switch

- Electrics: Goal Zero Boulder 30, 300-watt inverter

- Engine preheater and shower: Espar Hydronic D5

- Compressor: Viair 90

••••

“The Book of Independence works its magic like a bellows on the embers of wanderlust, inspiring us to break away from the norm, to slow down and smell the proverbial roses… or cow or elephant dung. It’s not about what you’ll do after you retire, it’s about what you do before you die.”

Chris Collard, Chief Editor, Overland Journal Magazine

Pablo Rey (Buenos Aires) and Anna Callau (Barcelona) also known as #viajeros4x4x4, have been overlanding the world non stop since 2000 on a 4WD Delica van. They mastered the art of solving problems (breakdowns and police harassment, between them) in far away places, while enjoying their nomadic lifestyle.

They’ve been 3 years driving through Middle East and Africa, between Cairo and Cape Town; 7 years all around South America, and 7 years going to every corner of Central and North America. They crossed the Southern Atlantic Ocean in a fishing vessel, descended an Amazon river in a 6 log wooden raft, and walked with a swiss knife between elephants in wild Africa. On the last two years they started to travel by foot (Pyrenees mountains coast to coast, two months) and motorbike (Asia), with the smallest lugagge possible.

Pablo has written three books in Spanish (one translated in English), many articles to magazines like Overland Journal and Lonely Planet and both are in the short list of the most respected latino overlanders.

¿When will the journey end? It doesn’t end, the journey is life itself.