294- Travelling thru Narco County |OVERLAND JOURNAL

© Pablo Rey, Overland Journal Magazine, Gear Guide Issue 2015

TRAVELLING THRU NARCO COUNTY.

International nomad Pablo Rey assesses Mexico’s world of cartels, farmers, fishermen, and cerveza fría.

The Mexican immigration agent was as clear as the customs agent who was as clear as the taco seller. The three of them shared the same words, the same advice, with the same stern face, “Don’t drive at night.” We were leaving the U.S. thru the Calexico/Mexicali border and instead of feeling unsafe for entering a country where the narcotics business is responsible for about 10,000 deaths per year, I was entertaining myself with the names of the bordering towns. Calexico was derived from names California and Mexico, and Mexicali from Mexico and California.

Should I have been worried? “Don’t drive at night” was an unfinished sentence. It lacked the portion that a friend from San Luis Rio Colorado shared with us while we were enjoying corn tortillas with pulled pork and cold Tecate in her backyard. She said, “There are civilian controls at night. Armed men stopping the traffic on the road to ask for documents and check the vehicles.” “Narcos?” I asked without realizing that this word should not even be whispered in Northern Mexico.

We had spent 21 months overlanding through Anglo North America and had just crossed into Mexico. Crossing the border meant going back into Latin America, a different world, one that was less than perfect and with more opportunity for spontaneity. I was eager to exchange the smell of burgers and fried chicken for the slightly salty aroma of innards wrapped in tortillas. I wanted to speak in my native language, listen to Latin American music, camp on a beach, and walk through fruit and vegetable markets that would never be clean enough for the health authorities north of the Rio Grande. I wanted to go back to a place where life was less predictable.

Our goal was to explore the Sonoran Desert, to see for ourselves if it was as beautiful as the deserts we’d come to love in Baja California. We knew that there would be military checkpoints on the road and policemen who would want to know what we were doing and where we were going. Maybe they would inspect our vehicle, searching for contraband we might have hidden in grandma’s pot or between the crates of books that we sell to help pay for our travels. The risk at these checkpoints, whether they were civilian or military, would be when our antagonists fringed on the extremes of boredom or tension. We would need to be calm and give them short, direct, and cordial answers. There is nothing more dangerous than finding yourself in the middle of nowhere with a bunch of armed people who are bored or stressed.

By the end of the second day we had travelled nearly 600 kilometers, and surprisingly, the police, army, and bad guys had been as absent as they had been in the U.S. Where was the “Mexican drug war” the American media had been parading on the nightly news, the one that had infected our excitement about traveling south?

..

If the earth were dissected into various parts -arms, legs, head, and feet- many would say that we were in the heart of a territory ruled by one of the best-organized narcotic cartels in the world.

..

With two hours of daylight left we decided to change plans and take a detour to Puerto Libertad in search of a palapa, a palm-leaf roofed hut, to camp in: The temptation to sleep on the beach had won us over. We needed only to ask the attendant at the Pemex station about the best route. “It is a dirt road,” he said, “You’d better take the tar road to El Desemboque and then the coastal road. People in towns on the way to Puerto Libertad have their crops and don’t like stranger. It is getting dark soon, you better go to El Desemboque.” We had a feeling he wasn’t talking about the usual crops of corn or tomatoes, but I didn’t ask any more questions. We turned down the long road to El Desemboque and I pressed down on the gas pedal.

If the earth were dissected into its various parts -arms, legs, head, and feet- many would say that we were in the heart of a territory ruled by one of the best-organized narcotic cartels in the world. At first glance, this region controlled by the Sinaloa Cartel was living a normal life, the same as any other part of the country. Nothing revealed that we were in a dangerous place ruled by a parallel power. We hadn’t crossed a border or passed through immigration or customs checkpoints, but somewhere ahead there was an armed civilian corps with its own justice system.

We didn’t know what would happen if beyond the next curve the road was blocked by men with guns. Could it be a bad situation? We couldn’t say, “Sorry sir, we didn’t know,” as we had been advised not to travel there. As the sun touched the horizon I stepped on the accelerator, abandoning our 90-kph routine. I wanted to cover the 105 kilometers of narrow tar road to El Desemboque before darkness could hide the area’s details. We didn’t want to be en route in Mexico at night…or so we’d been warned.

Sonora State Highway 37 is long and winding, like a noodle dropped on the ground. Only when the road dipped into a dry riverbed did I slow to the speed recommended by the various bullet-holed traffic signs. On the left, red rock mountains rose over a bushy desert, a visual barrier to the cultivated valleys of corn, hemp, prickly pear, poppy, and fruit trees. The landscape was rough and dry, and it seemed to be some time since the drug lords had invested in these rural and hidden lands.

The people working the plantations in this area are the poorest farmers, the ones forgotten by economists and politicians. But maybe they had realized that a crop of cannabis or poppy would provide the same profit as several years of growing corn. The chemicals needed to grown such crops weren’t a big problem. They could arrive hidden in the beds of 8-cylinder pick-up trucks, amazing beasts that were much more efficient than their horses or mules. The finished product, white bricks or green pressed bundles, could then be sent north in small aircraft that flew just high enough to avoid phone and power lines.

El Desemboque was too small to be in the guidebook that Anna was reading. I hadn’t seen a picture of this coastal town. No one had said if it was beautiful, ugly, dirty, or quiet. We only had the advice we were given earlier. We still didn’t know where we were going to spend the night and our destiny was uncertain.

The purest form of travel in my opinion is to move forward without knowing what you will find along the way. Throw the dice, let the chaos find order, and land on your feet like an old cat that has lost count of how many times its life has been saved, but here we could not sleep on the side of the road or turn off on a dirt track to camp in a place with no name—or between hills with names that are better to forget. I keep whispering one of my favorite mantras, we will find a place, hoping to invoke the magic of coincidences.

Two white lights appeared in the rear view mirror. They were intense and catching up with us quickly. My mine recited the Pemex attendant’s words. I pressed the accelerator further towards the floor, moving the speedometer needle to the supersonic speed of 135 kph, to the point that the steering wheel started to shake – the physical limit before the body of our 1991 Delica van would start to fall apart and leave pieces here and there. The lights continued to get closer. Was it someone with a bigger engine and more fear than we had? Maybe they were just in a hurry. They overtook us, leaving a silver trail on the road. In the distance, the silhouette of a roof appeared against the red sky and a green road sign announced we had reached El Desemboque. Night had fallen and the tar road turned into a dirt street.

In the darkness El Desemboque looked like a town inhabited by ghosts, its unpaved streets illuminated only by the light of a few houses. Shadows turned away and ducked into doorways when they heard the noise of our engine. A few men drank beer in front of a shop under a big Tecate sign, their faces showing curiosity and surprise.

In front of most of houses were boats painted in white and with sterns empty; I supposed it was safer for the engines to sleep at home. The street turned left, then right, and continued to a row of old structures at the edge of sea. After a confusing detour we saw a light in a backyard that opened to the sea. A yellow bulb hung over two men who were seated in front of a small building, eating from a pot with their bare hands. I left the engine running, got out, walked towards them, and said hello.

Their first words were the offering of food, freshly cooked crabs from the pot. Strangely, one of them asked if I was from Texas. I told them we were driving to South America and we were looking for a place to sleep. They offered me a beer, and by my second sip told me to park our van beside the table and that it was okay to sleep there.

During the last four days we had driven nearly 800 kilometers through the heart of Narco County. What happened to the “dangerous Mexico” we had been warned about? Where were the bad guys and the corpses that were said to be hanging from bridges? Where was the war that caused so much suffering and death?

After a year travelling through most of Mexico we’ve learned that, like most other places in the world, we only had to be cautions of common thieves. The drug war is certainly present, but Narcos typically don’t mess with foreigners. They have other business, business that is much more important and profitable than hassling tourists.

That night we ate crab and drank beer with Pedro and José, our new friends. The following day I learned how to filet flat fish by imitating the precise movements of their knives. I helped them retrieve fishing nets they had left overnight in the Sea of Cortez, which were full of sea snails and more flat fish. We shared stories and we laughed. We could have encountered Pedro and José in Mexico City, Michoacán, Cancun, Monterrey, or Sinaloa, on the Pacific or the Atlantic coast, or on a forgotten beach in Narco County. Mexico is big, its people kind and friendly, and we were welcomed with open arms and lots of beer.

••••

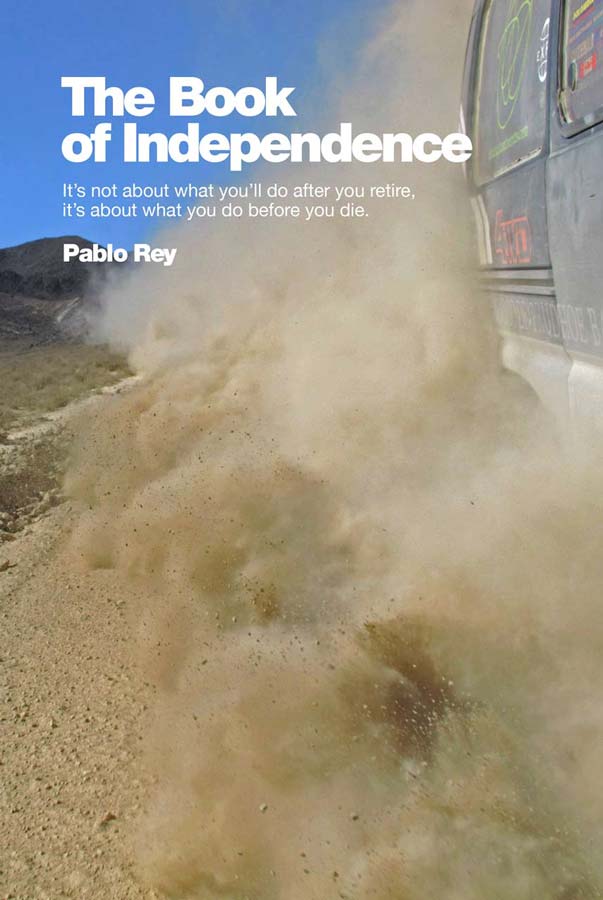

“The Book of Independence works its magic like a bellows on the embers of wanderlust, inspiring us to break away from the norm, to slow down and smell the proverbial roses… or cow or elephant dung. It’s not about what you’ll do after you retire, it’s about what you do before you die.”

Chris Collard, Chief Editor, Overland Journal Magazine

Pablo Rey (Buenos Aires) and Anna Callau (Barcelona) also known as #viajeros4x4x4, have been overlanding the world non stop since 2000 on a 4WD Delica van. They mastered the art of solving problems (breakdowns and police harassment, between them) in far away places, while enjoying their nomadic lifestyle.

They’ve been 3 years driving through Middle East and Africa, between Cairo and Cape Town; 7 years all around South America, and 7 years going to every corner of Central and North America. They crossed the Southern Atlantic Ocean in a fishing vessel, descended an Amazon river in a 6 log wooden raft, and walked with a swiss knife between elephants in wild Africa. On the last two years they started to travel by foot (Pyrenees mountains coast to coast, two months) and motorbike (Asia), with the smallest lugagge possible.

Pablo has written three books in Spanish (one translated in English), many articles to magazines like Overland Journal and Lonely Planet and both are in the short list of the most respected latino overlanders.

¿When will the journey end? It doesn’t end, the journey is life itself.

Me ha encantado la entrada. Mexico es un país maravilloso y lleno de buena gente, que te ayuda y te acoge siempre que pueden. Eso sí, hay que tener cuidado con ciertas cosas y ser precavido. Yo el tiempo que estuve no tuve ni vi ningún problema, pero sí conozco a gente que han sido atracados por conducir o caminar solos por la noche. Pero vamos, como dices, los narcos tienen otras cosas que hacer que liarla con los turistas y el país está lleno de gente maravillosa. Love mexico!

Que refrescante leer sobre mi México lindo desde los ojos de alguien que busca belleza y bondad en la gente y no se deja guiar por el miedo que propagan los medios de comunicación. Desde ahora soy fan de sus aventuras que seguiré como punto de inspiración y referencia para nuestro primer viaje alrededor del mundo. Gracias!

Hola Ana, ya estamos de vuelta por tu México querido, y por nuestro México querido. Los países son la gente en la calle, no los políticos, ni los sitios arqueológicos, ni los equipos de fútbol. Nos gusta la gente de México. Junto con Perú, son nuestros países preferidos de América! Bienvenida a La Vuelta al Mundo en 10 Años, que ya son 15 y medio!