3 Gringos, 10 Days and a 6-Log Raft | OVERLAND JOURNAL

© Pablo Rey. Published on Overland Journal, Winter 2011.

© Pablo Rey – (Lee esta historia en castellano en 3 Gringos, 10 días y una balsa de 6 troncos)

ADVENTURE

Adventure is starting something without knowing how you are going to finish, and usually comes with a large dose of adrenaline and a small measure of fear. It is to venture down a new and unfamiliar path, often without being completely prepared. It is quitting your job to star a new life. Adventure is about abandoning self-doubt and personal fears, leaving doors open to chaos as it may come, and walking to our final appointment with death, feeling that life as we lived it was worth the price.

Many of the world’s greatest adventures have begun as a casual suggestion, a few words between two sips of beer, a recessed thought that slips out from your memory files, or a farfetched idea picked up by a stranger who was close enough to overhear a conversation. “What if we did this…? And why not have a… And then we’ll climb the…”

It is a pivotal moment of an adventure: when an idea morphs from an absurd and nebulous fantasy, to intention. This is minute zero –you are not yet away from home but you have already mentally checked out (in my case, I’m probably already getting into trouble). When you realize you have an accomplice, and that your private delusion is shared by another (this is Anna, my traveling partner for eleven years), any thoughts of backing out, or (God forbid a verbalization), and you would be eternally labeled as a city-slicking chicken.

The details of the vision don’t really matter –It could be getting lost in real Mexico (further south than the North American colony of Baja), sky diving with skis into the crater of a snow-covered volcano (better if it is active), or pointing your dual-sport towards the far reaches of the Dempster, the Dalton, or Pan American Highway. Wherever your end of the world is, Tierra del Fuego, the Cape of Africa, or the Moon, the important thing is committing yourself to finding it.

In our case, the words that slipped between a glass of beer and my lips, an inconceivably ludicrous thought that I’d regurgitated from that foolish part of my body called the mouth, had become an insane but semi-plausible plan. At first thought, the idea was so simple that it seemed possible. We simply needed to drive our ultimate overland machine, a Mitsubishi L300 4×4 we call La Cucaracha, to the last village on the most remote muddy two-track in the Amazon jungle, and keep going –on a wooden raft.

Yes, a wooden raft. The same type of rickety, hand built craft that Tarzan used to ply the rivers of Africa, and similar to the tatty and unstable lashed-log vessels used in the Yukon during the gold rush. It had been 470 years since the first white man, Spanish explorer Francisco de Orellana, navigated the Amazon River from the Andes to the Atlantic Ocean. With Orellana in mind, our sortie would need to be on a traditional craft: no fiberglass or carbon fiber here.

It would be undoubtedly be safer to do this trip in a modern kayak or canoe; to have a detailed map of the region rather than a photocopy of a free tourist pamphlet (folded in fours so it can fit in my pocket); or to delay the trip until we found the appropriate equipment. Any of these might be acceptable cause for most people to nix the whole idea.

But it is now or never, and from time-to-time it is good to do something crazy. How else could we consider stepping onto a wooden raft, in a remote jungle, on a river that we don’t know (though we do know it is full of caiman and anaconda)? We are without a guide, satellite phone or any chance of being rescued if things go wrong. Armed only with an African-made machete and a Swiss-Army knife, crazy… yes, we must be crazy.

There are two fundamental reasons to continue on with the plan. The first is that we have mentally committed ourselves to the vision. The second is that if we really want to explore the depths of the Amazon jungle, short of joining an expensive tourist boat cruise, this is the way. Anna and I will park La Cucaracha, the place we have called home for the last eleven years, and take a waterway less traveled.

THE PRICE OF ADVENTURE.

This is our fifth month in Peru, one of the most fascinating countries in South America. During our time here we’ve explored 2000 kilometres of coastal deserts, flown over the mysterious geoglyphs of the Nasca lines, and walked through the ancient Inca ruins of Machu Picchu. In the process we’ve followed railroad lines across the Andes several times on roads over 5000 metres abouve sea level (yes, that’s 16.500 feet). All were exhilarating and breathtaking, yet one of our greatest adventures was yet to come.

It was in the city of Cusco, ancient capital of the Incan Empire, where we met Mauro, a Uruguayan volunteer who had been helping with the educational needs of children in the Peruvian Amazon. Mauro had invited us to visit him in Salvación, a village of about 700 inhabitants in the state of Madre de Dios. It didn’t look so distant on the map, about 300 kilometres; but the line identifying the road, became thinner and thinner before disappearing in a massive area of green –perfect. It ended up being a 12-hour trek on a tortuous dirt track full of combis (passenger vans) and trucks driven by kamikazes who apparently believed in eternal life.

Mid trip we crossed an invisible border into a land of settlers in permanent struggle to conquer the jungle and convert it into their vision of civilization. These were rough men, hungry for a plot of land to extract timber, produce maize, raise cattle, and mine for gold. What was left of nature resembled a decaying and mutilated corpse of what had been. The once-thriving aboriginal tribes of the region were now hollow-eyed and dispirited, decimated by alcohol and other imported vices.

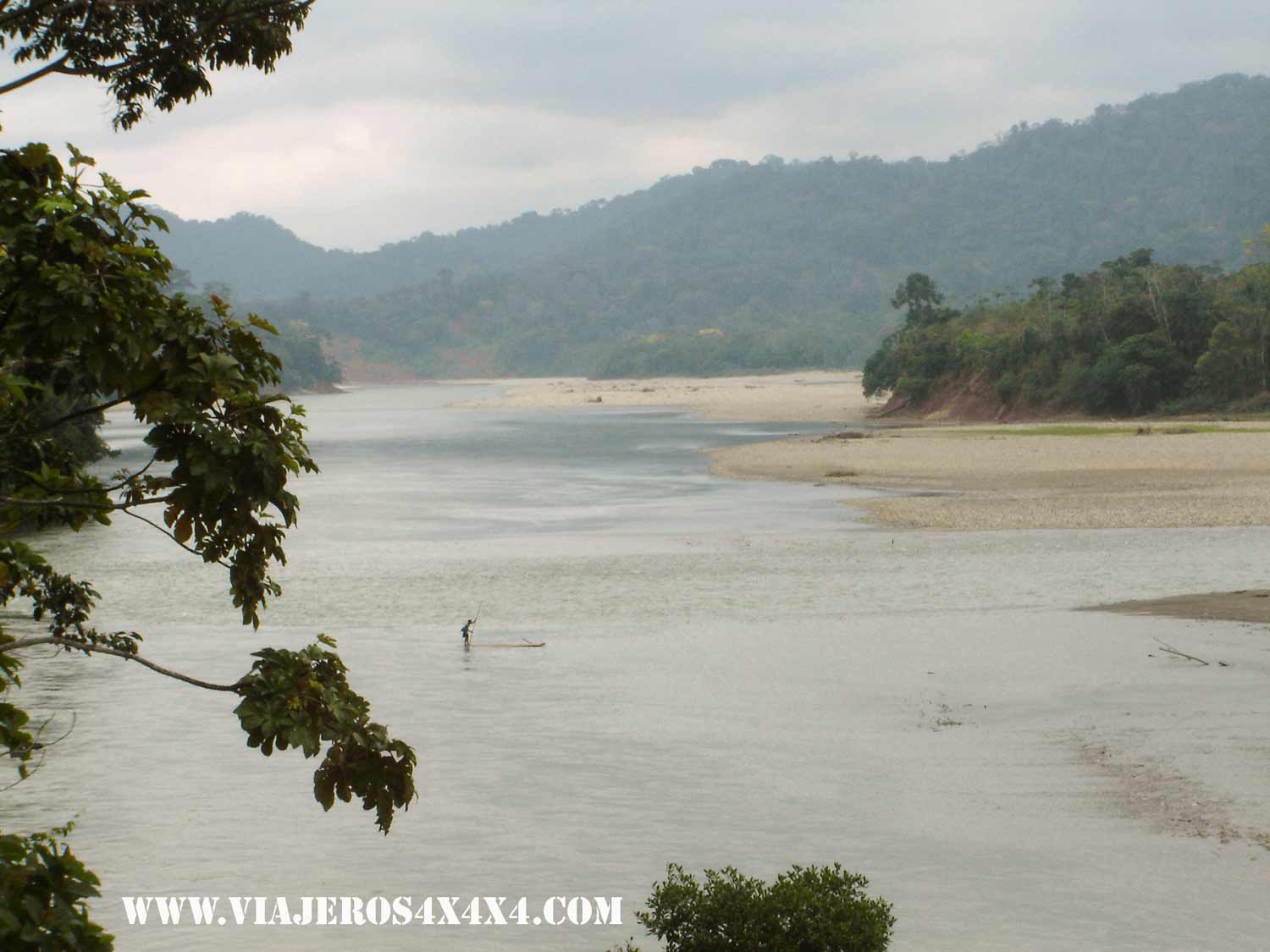

The raft idea arose in the second afternoon in Salvación as we sat on the banks of the Río Alto Madre de Dios. This was moment zero. The river’s cool waters flowed fast, like an artery into the heart of South America. Though its final destination is the Atlantic Ocean, the river’s course meanders to the north and south as it drifts towards Bolivia and Brazil. There it becomes Rio Madeira, one of the most important tributaries of the Amazon. But we were not aiming to go that far. Our quest to see a private slice of the Amazon would need to be done in just 10 days, ending in the mining town of Colorado. Once there, we hope to find a truck to bring us out of the jungle and back to Salvación. As the crow flies, the distance is about 200 kilometres, not counting bends of the river, accidents or occasional piranhas -10 days should be enough.

“Mauro, have you ever driven a raft? I guess you have a driving license…” I asked, “It is important that someone knows where the steering wheel and the brakes are.”

“Yes, I’ve driven a raft in a cocha… once…” Mauro replied.

This was not a confidence builder. Cochas are long lakes surrounded by jungle; old watercourses carved out by the river during the intense rainy season, then abandoned as the waters ebb. A cocha is calm with no current… there are no submerged trees or boulders to run into. It is the perfect place for a contemplative drift on a sunny day; however, this wasn’t what we had in mind.

Two days later we arrived in Shintuya, a small village of the Harakmbut tribe. Though Shintuya is only 40 kilometres from Salvación, it was a two-hour drive on a road that again, does not appear on any maps. The entire village is comprised of about 40 houses constructed from branches and adobe brick. There is also a Christian mission, a bar, and three stores that sell rice, oil, cookies and sundries.

This is where we meet Leoncio, the official raft builder of the town. He wanted 24 hours and 100 soles to do the job. About $30 U.S. dollars, this was the high price for the specialized gear we needed. He would build the raft with trunks from a tree called topa, an extremely buoyant white wood, and assemble it with nails, or spikes, made from the chonta tree, a very hard and dark wood. The design (patent pending we were sure) included a small table built of reeds, placed in the centre of the raft to be used as a storage trunk. Our craft included two tanganas, long poles used to propel and steer our classic Flintstones vessel. We added two paddles, which we rescued from an old and decaying kayak, and that was it. A raft is a raft. You can’t choose the color, the extras, or the leather upholstery. You can only pick the piece of raw wood that will serve as your seat.

The following morning we found our brand new raft anchored in a nearby stream. It was four metres in length and just a metre in width. In one word, it was small. While we were loading the equipment (a tent, sleeping bags, food for 10 days, a bottle of rum, clothes, Anna’s grandmother’s pot, a bundle of bananas, and a gallon of mosquito repellent), some of the villagers came out to see us off. They pointed at the raft, whispered to each other, and shook their heads from one side to the other. It felt like they were saying good-bye… forever.

The priest asked, “Well… if you are not back in a month I inherit the van, right?”

“This raft is not okay, you should tie the trunks with wire. If you’ve never driven a raft you are going to hit many large stones in the river.” says Miguel, the person in charge of (sometimes) watching out for illegal deforestation.

“You have to better secure the storage trunk, the bark strings normally get loose when they become dry.” Miguel’s assistant points out.

“Wouldn’t it be better to have one more log?” commented Laia, a volunteer from Barcelona.

“Thanks to you all for your supportive words and optimism. I appreciate it. It is not a boat, but it floats. How do we name it?” I ask, while Mauro and Anna paused from piling our provisions on the sand. Silence… Everyone looked with skepticism and concern at our new overland, (well, not really) our overwater vehicle. We had exchanged a 4WD for a log raft, and dirt roads for an aqueous conduit into the unknown. Suddenly, Anna starts laughing. “What if we call it Titanic?” Never before was a project undertaken with such questionable odds of success.

IN THE AMAZON, THE CARNIVORES ARE SILENT.

August is at the middle of the dry season: the best time of year to ply the rivers of the Amazon basin. The morning is sweltering hot and heavy clouds shadow the hills of the opposite shore. It is 11 a.m. We push the Titanic to the main flow of the river and drifted away from civilization. Que sea lo que Dios quiera (May God’s will be done).

The first thing we notice is that a log raft doesn’t react like a car. It handles like a slow and heavy tanker sliding along a huge oil slick; you move at the same pace, but in different and uncontrollable directions. A familiar voice inside my head keeps asking me. “Where have you left your brain? With the enormous effort that men have made to send a vehicle to Mars, you are travelling as if you are living in the Stone Age…” The voice is that of my sedentary devil that never stops getting into my personal business.

After the first moments of excitement, the silence becomes overwhelming. No one speaks a word as we drift with the flow of the river. From time to time we dip a paddle to align our craft with the flow, and maybe win back a bit of navigational confidence.

On both sides of the river, trees dressed with green, yellow and red leaves obscure the rest of the world behind a thick veil of tangled vines. All that can be heard is the voice of the jungle: the chatter of howling monkeys and the sweet harmonies of the Amazon’s intensely colorful birds. Without doubt, we have entered another world. We’ve stepped into an ancient church, into the original and universal temple of humankind.

The river splits as we move ahead; it is not easy to guess which arm is the correct one. We are three people, and there are always three chances: right, center and left. If we veer to the right, the current will drive us against the sharp reeds and branches of the shore. If we stay in the center, we might get stuck on the shallow rocks; the left arm may lead us to a dead-end lagoon. A small gang of squawking parrots carves a path between the shoreline trees, seemingly to laugh at our dilemma; it is not easy to come to an agreement.

The first rapids come to sight at the next bend of the river. The sound is of a roaring beast charging wildly in our direction. What to do? The crystalline water reveals the bottom of the river moving at full speed, just a few centimeters under our feet. It is as if we are dancing over a horizontal climbing wall, our small craft pitching and rocking with every undulation of the current. The rocks follow one another like a violent horizontal hailstorm. We avoid branches and tree trunks, treacherous whirlpools, and frothing puffs of toxic foam (the result of human pollution). Flying over the river, we paddle to the right to evade a large rock; maybe the same one we eluded before. Then it appears in front of us to bite again (it must have been the first rock’s cousin). Water bursts into a foaming spray as it collides with the uneven bow of the Titanic. Anna and I paddle from the front in an attempt to align ourselves with the flow. Mauro, standing in the back, pushes the tangana against the elusive river bottom. The Titanic insists on offering its cheek to the current rather than its chin. Round rocks, the size of human skulls, scrape the bottom, catching the tangana and snapping it in two. But we have cleared the rapids and are safe. I sand up on from my crouched position on the bow to celebrate; slipping on the wet logs I fall into the river. We haven’t seen any caiman yet. Hopefully, this will not be the time of our first sighting.

Mid-afternoon, four hours after our departure, we pull out near the mouth of a dry creek. After mooring the raft on the shore and setting up the camp high enough to avoid a flash flood, I look for some dry wood for a campfire. It is not cold, but hot coffee helps to warm the soul, wet under a layer of soaked clothes. Midday coffee is a ritual that will be repeated over the next 10 days.

With evening comes the rain. It is a warm rain, but we retreat into the tent for shelter. I think to myself, “Isn’t it the dry season? Is the river going to rise?” We are close to the equator and the hours of daylight and darkness are fairly shared. But nights, full of lightning and noises foreign to us, seem longer. I think of nights in Africa. I miss the sound of snorting hippos, the roar of lions surrounding a baby elephant that cries hopelessly for its mother, and the hysterical laughter of hyenas beyond the edge of the firelight.

Half an hour before dawn, the natural alarm clock of the jungle sounds. Birds respond to the first light and begin singing as if in a choir. As each awakens and joins in, it transforms into a symphony. Monkeys stretch their loins and screech as if to celebrate surviving another night in nature’s food chain. The sounds of cu-cu and aak-aah, reach the point of ecstasy by the time the first rays of light kiss the upper reaches of the canopy. I step out of the tent to look around. We are far from anything that would be considered modern –we are in paradise.

It rained last night, but the river is still in place. Next to my bare feet there are fresh tracks in the sand. Somewhere in the night, the otorongo, tiger or jaguar visited. At this point, the nomenclature doesn’t really matter; the feet of a large cat made these. In Africa, at least you know where your enemies are; in the Amazon the carnivores are silent.

THE LAST STRONGHOLD OF THE INCAS

By 10 a.m. the sun hits us at full force. Squadrons of insects, looking for breakfast, fill the air. A tiny white fly seems to have a fetish attraction for Anna’s arms. Mosquitoes circle as if in a landing pattern, waiting for an unsuspecting moment to dive in for the kill. We swat away the blood-sucking Dracula flies, but they won’t surrender. In a calm spot of the river, a beautiful spider walks over the water like an eight-legged messiah. On the shore, a fat and lazy tapir, perfectly designed by nature for a barbecue, lumbers through the reeds and takes cover behind the first line of vegetation.

Although the river presents new rapids today, our advance is slow. A peque-peque, a small canoe with three passengers and some cargo, progresses against the flow, propelled by an outboard motor. It has just left the right shore, where empty petrol barrels mark the boat’s presence. About half an hour walk from the left shore we visit Shipitiari, a remote village where people still speak machiguenga, the indigenous language of the region. Shipitiari remains hidden in the heart of the jungle, quite possible one of the only places where the knowledge and tradition of this special culture might be preserved. It is also the home of Noemí, a wild-eyes, seven-year-old girl we met in Salvación.

Lovely and hyperactive, and with several of her baby teeth missing, Noemí holds the extraordinary skill of climbing trees, vines or people; up one side, down the other, sideways or upside-down and head first, she never falls. It is said that her father, the tribal shaman, gave her bear blood when she was a baby, and that she inherited the strength and agility of the donor.

Deeper into the jungle is Manu, one of the most impressive national parks in South America. Created in 1973, Manu, a World Heritage site and Biosphere Reserve, is a primeval paradise that protects sixteen different ecosystems. Somewhere beyond the last Machinguenga settlement and buried under layers of undergrowth, awaits the mythical golden city of Paititi. Hidden in this impenetrable jungle, Paititi is said to be the last stronghold of the Inca people. For four centuries beginning with the release of a report by Jesuit explorer Andrés López in 1600 AD, archaeologists and treasure hunters from around the globe have searched for this lost city of gold.

THREE GRINGOS TRAPPED IN THE RIVER

It is day four on the river and my body is riddled with swelling bites, red bruises and irritated lacerations. Some type of invisible insect has settled in and is nesting on my testicles. I can’t stop scratching. Our return to nature is turning me into a chimpanzee. But at this moment I’m excited and wouldn’t exchange my weary state for anything.

The name of our ship, the Titanic, has almost faded from the hull. Leoncio, the architect of this fine vessel, failed to inform us of one important detail, logs absorb water. Though still floating, we are now receiving all-day aqua therapy on our feet and ankles. This aside, if fate were to deal us cards again, optimism would be ours. I remember the sense of safety we had with our wheeled home, La Cucaracha: abouve all, the feeling of being dry. In a raft you get wetter than riding a motorbike in Florida during a hurricane.

From the left, a twenty-metre-wide river joins our course. The transparent waters of the Alto Madre de Dios mixes with the red, sediment-rich flow of Río Manu. “Treeeeeee!!!” Mauro screams from the stern, catapulting me back to the moment. We paddle frantically to overcome the flow that is driving us towards the open jaws of a twisted and sunken tree. All is in vain; it is our Moby Dick of the jungle. The river is deep, flowing swiftly, and the impact is hard. The Titanic begins to lean to one side, threatening to flip over and discard us into the water. We are stuck between the fast flowing current and a tangle of dead trees and branches. We have no lifeboat. Well, on the other hand, we are standing on the lifeboat.

Mauro plunges the tangana into the water looking for a pivot point to secure the raft. Anna jumps onto the tree, half her body underwater, and keeps the raft from capsizing. In my usually helpful way, I stand up, turn on the video camera and begin filming. I think they both want to kill me.

Thirty seconds pass; they struggle with Moby Dick and I document the scene. Anna swears to drown me if we survive. Locating the machete we bought in Uganda, I hack off one of the branches to no avail. I grab a rope that is tied to the Titanic and leap into the water. Grasping a tree limb, I pull the rope to straighten the raft. Anna pushes desperately against the branch that is pinning us to the flow of the river.

Three children watch our reality show from the shore. What attracts their attention is not the risk and danger of the situation, but the fact that we are three gringos, in the middle of the river on a log raft, and without a guide. (It doesn’t matter is we were born in Europe or South America; if we are white skinned, or non-Indian, we are considered gringos to the Indians.) A few minutes later the raft slips between the dead trees like a small branch dragged by the current. We are free.

MINERS, THE WILD WEST, AND BEER.

We pull out at the village of Barrancas de Boca Manu, the midpoint of the trip. Rising from a sandy beach, small wooden cabins stand in scattered disarray, each of which seems to be a small store with sundries, food, and alcohol strong enough to start an engine. In a place like this, a small village far from a power grid or cell tower, we can feel the calmness. There is not much to do except lay in a hammock, watch the river drift by or observe the dance of the flies.

Boca Manu marks the beginning of a more difficult portion of the river. We have no rapids to deal with, but the river has become wider, deeper and slower: we now must paddle. Through the heat of the day, we navigate endless horseshoe bends; near-perfect circles of several kilometers in diameter, all of which seem to end not far from where they start. The hours tick by; today turns into tomorrow. In real distance we don’t seem to cover much ground.

The jungle presents new surprises every day. Overhead, a parrot passes by, sporting a rainbow tuxedo. Kingfishers carve turns over the river at full speed, in search of their next meal. There are herons on the shoreline, and plants that recoil when I touch them. A turtle pops its head out of the water and overtakes us. Next to the raft is a tree trunk that resembles the tail of an airplane; maybe evidence of another of Jimmy Angel’s wild South American adventures.

Day Eight: Today we see the first gold miners of the river. With dredges, water pumps and dragging belts, they work the edges of the river and adjoining creeks, turning them to a murky soup of brown. They do not see us as we silently drift by their chaos. At sunset we camp under an enormous tree, while the river continues to slip by like a silent mercenary in the night.

Day Nine: For the last several days we have been drinking the delicious but turbid water of the river, which has an almost smoky flavor. Now that we are approaching the town of Colorado, a significant mining area, this is probably not such a good idea. We know we are getting closer, as river traffic has increased. Peque-peques (small boats) ply the river, transporting supplies and laborers to different mining interests, which now occupy larger portions of shoreline. It was our desire to get lost in the pristine and untouched Amazon jungle, the real Amazon. We have done this, and it is a beautiful and wild place. We are disappointed to see the chaotic mess before us; how man is rapidly transforming paradise into a polluted hell.

Colorado itself is reminiscent of a Wild West town, but in deep-jungle South American style. Rustic wooden buildings line the narrow dirt streets, 24/7 signs hang above gold buyer shops, tuk-tuks speed by, kicking up dust which swirls through numerous Inka Cola stalls, and prostitutes wait for their workday to begin when the sun sets. Almost everybody wears a T-shirt, which they receive for free, of the political party that unites rubber tappers, loggers, miners, and farmers –the people who want to extract the jungle’s resources and leave nothing but toxic waste and deforestation.

After finding a hostel, we step into a local saloon for a cold beer, clinking our

bottles in celebration of our accomplishment –an obsurd and crazy plan to see the Amazon that became a reality. We contemplate the number of people who dream to live a life of adventure, yet are held hostage by fear: it is sad. Fifteen days ago we didn’t know this adventure was written in our destiny –An Amazon River on a six-log raft? Yeah, right.

We now need transportation back to La Cucaracha. Our trusty 4WD must be lonely without us, and anxious to continue north on the Pan American Highway towards Deadhorse, Alaska. There are no busses or taxis here; the only way out of Colorado is to catch a ride on top of a transport truck (Amazon taxi), then get on a river boat, followed by another truck ride. “Or,” I say between two sips of beer, “We could paddle back up Río Madre de Dios…” Anna sets down her beer and closes her eyes as I start talking again. “What if we….?”

•••••

Pablo Rey (Buenos Aires) and Anna Callau (Barcelona) also known as #viajeros4x4x4, have been overlanding the world non stop since 2000 on a 4WD Delica van. They mastered the art of solving problems (breakdowns and police harassment, between them) in far away places, while enjoying their nomadic lifestyle.

They’ve been 3 years driving through Middle East and Africa, between Cairo and Cape Town; 7 years all around South America, and 7 years going to every corner of Central and North America. They crossed the Southern Atlantic Ocean in a fishing vessel, descended an Amazon river in a 6 log wooden raft, and walked with a swiss knife between elephants in wild Africa. On the last two years they started to travel by foot (Pyrenees mountains coast to coast, two months) and motorbike (Asia), with the smallest lugagge possible.

Pablo has written three books in Spanish (one translated in English), many articles to magazines like Overland Journal and Lonely Planet and both are in the short list of the most respected latino overlanders.

¿When will the journey end? It doesn’t end, the journey is life itself.

Hey there! This is my first comment here so I just wanted to give a quick shout out and say I really enjoy reading through your blog posts!